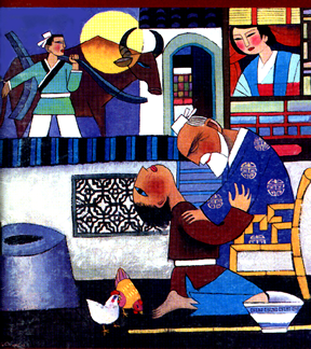

He Qi, The Prodigal Son, 1996

A Study Guide by Lee Magness

Here's a look at the story of the Prodigal Son from the perspective of Chinese culture. Many features of this modern painting of the parable are familiar to us--the penitent prodigal, the welcoming father, the hard-working older son. And although there is no mother mentioned in the parable, she is often depicted in paintings. But there are also a number of features unique to this depiction, notably those which envision the story in a Chinese context.

The artist is He Qi (pronounced "huh chi"), a contemporary Christian Chinese artist. He came to faith as a young man, moved initially by a painting of the Madonna and Child by Raphael, and he continues to express his faith through his paintings of scenes from throughout the Bible. Check out his websites for more information about his biography and to explore his other Biblical paintings--heqiart.com and heqigallery.com.

Let's explore the painting. Consider the following questions:

1) What is the artist trying to express by the father's appearance, posture, clothing, etc.?

2) What is the artist trying to express by the younger son's appearance, posture, clothing, etc.

3) What is the artist trying to express by the presence of the older son and mother?

4) Identify the typically Chinese features of the painting. How do they enhance our understanding of the parable?

5) Identify interesting artistic features of the painting? How do they enhance our experience of the story?

An Interpretation ~

On the surface He Qi's depiction of the parable of the prodigal son feels very familiar. An elderly but well-dressed father warmly welcomes his wandering son home with an earnest embrace. The son kneels and clings to his father, his clothes worn and frayed, his posture penitent. The reunion takes place in the courtyard of the father's sumptuous home. The strapping elder son makes his way in from the field as the sun sets at the end of a long day. These words could be spoken of any number of paintings of the prodigal son but they barely do justice to this painting.

Consider first the father. He sits, not on the floor, but in a chair of rank, the noble master of his estate, wearing a beautifully embroidered jacket, his white hair and beard dressed traditionally, bespeaking his age and dignity. He bows, eyes closed, controlling the overwhelming emotion he feels at the return of his beloved son. A smile bends across his weathered face.

Notice next the son. He wears the clothes of a peasant farmer and lays aside the staff of a wanderer. The knees of his trousers are worn through, the hems of his pant legs are in shreds. His sandals are long gone, worn out from years of toil and travel. His fingers are splayed, clinging desperately to the embracing arms of the father. He kneels of course, not as unusual in an Asian context as in Western culture, but still suggestive of respect and perhaps repentance. Instead of a traditional bow before his offended but forgiving father, He Qi offers us a head flung back, eyes to the skies. It suggests pain and grief over his past treatment of his father as well as penitence.

The older son is the picture of health and strength. His hair is adorned in the same traditional way as his father's. In a triumph of artistic design the ox's horns circle in mimicry of the setting sun and the sun spot-lights a shape that doubles as the mountain on the horizon and the shoulder of the beast of burden. The son shoulders his plow as he guides the ox back to the barn for the night, his right arm flung out in a gesture that suggests, "What's going on here" What's the meaning of all this?"

The rest of the scene might appear to be domestic filler--the chickens peck about the courtyard, the cloistered mother looks out past the paneled doors. But two images have special significance. On the left is the well from which the family draws its water, central to the compound in which they live and the source of their sustenance. On the right sits a bowl of rice, the staff of life in Chinese cuisine and culture. When a family member who has gone to the city to work comes home for a special holiday, the family first offers them their fill from a bowl of rice and gives them to drink from the family well. These acts symbolize the recognition and restitution of the child to his or her rightful place in the relationships that constitute the family.

I appreciate these two symbols that He Qi has incorporated in his artistic depiction of the parable. They remind us that the younger son has not only returned to the father, but to the family. They remind us that he is not only forgiven, but restored, reconciled to his rightful place within the family. From now on, when I envision the reunion scene of the parable of the Prodigal Son, there will be in my mind's eye a cool well in one corner and a warm bowl of rice sitting in the other, waiting to make me feel fully forgiven, finally home.