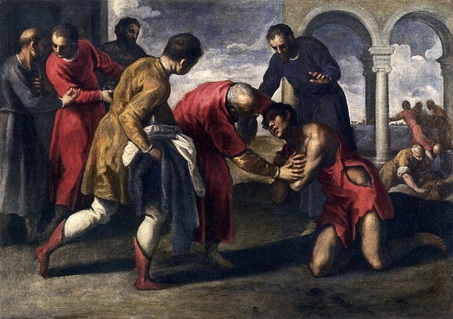

Palma Il Giovane, Return of the Prodigal, 1595

A Study Guide by Lee Magness

Palma Il Giovane (Palma the Younger) (1550-1628) was an influential Venetian painter, a later contemporary of Tintoretto, who learned his craft by copying Titian's masterpieces. He quickly earned commissions from the Doges in Venice, from Rome, from across north Italy, and from as far away as Prague. He specialized in Biblical and mythological subjects, including two paintings on the parable of the prodigal son—”The Amusements of the Prodigal” and this painting, “The Return of the Prodigal.”

Use the observations and questions below as you reflect on this fascinating work of art.

Use the observations and questions below as you reflect on this fascinating work of art.

Encountering the Prodigal Son in the Art of Palma Il Giovane

Reflection

1) This painting is one of two painted by the Italian artist, Palma the Younger. This one comes from 1595. Notice

the neoclassical setting, especially the columns and arches.

2) Identify the scene in the parable being depicted here? Why are artists so drawn to this scene in the parable?

3) Study the father and the younger son. How might we interpret their postures and gestures. What is suggested

about their attitudes and their relationship?

4) Study the other figures in the painting. Just about everyone is on the move. Who are the larger figures

surrounding the father and the younger son? What are they holding and doing?

5) Study the smaller figures on the right. Who are they and what are the doing?

6) Where is the older son in this painting? How does the artist depict his attitudes and actions?

Response

Write a short essay sharing your interpretation of the painting or write a short meditation on the meaning of the

parable as illustrated by this painting.

An Interpretation ~

In a world awash in rich blues and reds, every figure in “The Return of the Prodigal” (1595) is on the move, actively attending to the return of the lost son. He kneels, strong of body but bent, arms crossed, face upturned, pleading, suppliant, repentant, clothes once rich now rent. The elderly father, the central figure, bends low, embracing his back, hand on hand, to welcome and console his son. The rest of the household has been mobilized by the father’s commands. The servant in the foreground brings fresh robes, while the one behind bends to help. Back and left two servants examine the ring. Does the one in the red hold new sandals? To the right two servants slaughter the brown calf. Under the classical Ionic portico, three more set a sumptuous table, white cloth and all. Even the clouds scud by above the dramatic scene.

Only one figure out of twelve remains static, deep in shadow. In the back, third from the left, one man stands, frozen amid the flurry of response, recalcitrant. It is of course the elder brother. He needs speak no word. His dark face communicates his disdain. He is unmoving, because he is unmoved.

Reflection

1) This painting is one of two painted by the Italian artist, Palma the Younger. This one comes from 1595. Notice

the neoclassical setting, especially the columns and arches.

2) Identify the scene in the parable being depicted here? Why are artists so drawn to this scene in the parable?

3) Study the father and the younger son. How might we interpret their postures and gestures. What is suggested

about their attitudes and their relationship?

4) Study the other figures in the painting. Just about everyone is on the move. Who are the larger figures

surrounding the father and the younger son? What are they holding and doing?

5) Study the smaller figures on the right. Who are they and what are the doing?

6) Where is the older son in this painting? How does the artist depict his attitudes and actions?

Response

Write a short essay sharing your interpretation of the painting or write a short meditation on the meaning of the

parable as illustrated by this painting.

An Interpretation ~

In a world awash in rich blues and reds, every figure in “The Return of the Prodigal” (1595) is on the move, actively attending to the return of the lost son. He kneels, strong of body but bent, arms crossed, face upturned, pleading, suppliant, repentant, clothes once rich now rent. The elderly father, the central figure, bends low, embracing his back, hand on hand, to welcome and console his son. The rest of the household has been mobilized by the father’s commands. The servant in the foreground brings fresh robes, while the one behind bends to help. Back and left two servants examine the ring. Does the one in the red hold new sandals? To the right two servants slaughter the brown calf. Under the classical Ionic portico, three more set a sumptuous table, white cloth and all. Even the clouds scud by above the dramatic scene.

Only one figure out of twelve remains static, deep in shadow. In the back, third from the left, one man stands, frozen amid the flurry of response, recalcitrant. It is of course the elder brother. He needs speak no word. His dark face communicates his disdain. He is unmoving, because he is unmoved.