Janknegt's Two Sons, an Interpretation

by Lee Magness

Introduction

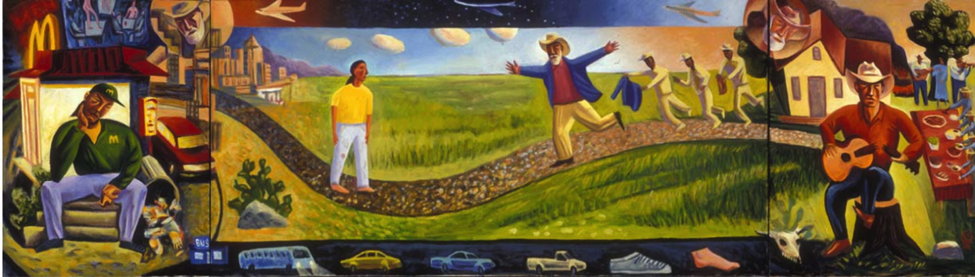

What we see before us is a triptych, a three-panelled painting common in the history of Christian art. The artist of our triptych, from 2002, is James Janknegt, a contemporary American Christian painter from Austin, Texas. And the subject of the triptych is the Parable of the Prodigal Son. Just to get our bearings, let’s identify the three scenes our artist chose to illustrate Jesus’ story. On the left, from early in the parable, the younger son sits in the far country. In the center, from the middle of the parable, are the father and the servants, welcoming the younger son home from his urban exile. On the right, the older son sits in a far country of his own making, while the welcome-home cookout goes on in the background. Janknegt entitled his provocative painting, “Two Sons.” To his credit, the title recognizes that there are two sons in the story, a fact overlooked by many artists and even some preachers. Even so, I’d give it a different title. I’d call it “the Persistent Presence of the Father.”

Analysis

In the left panel we meet the younger son already in the far country. He has already demanded his inheritance, and liquidated his assets, already fled to the far country, and “squandered his substance” (a pregnant phrase if there ever was one). He has already found himself without resources and without recourse, without finances or friends or family, famished, trapped in a country not only far but beset by famine. Janknegt offers us a younger son already desperate, already despondent. The dejected son sits surrounded by the evidences and effects of his life in the far country. The far country is a far city; a red car cruises the streets amid skyscrapers that dominate the urban landscape. A billboard advertises the strip clubs around the corner, the sight of his debauchery or the object of his daydreams. He sits on the steps of the Golden Arches Cafe, his pig pen, dressed in the uniform of his below-poverty-level job. He’s been rooting, like a pig, through a tipped-over garbage can, hoping to ease his hunger on Happy Meal scraps. He ponders his condition, head cocked, chin on hand, eyeing the sign at a bus stop, a way home perhaps. All in all an interesting modern depiction of the plight of the prodigal!

But there looming in the upper right corner is something provocative--the head, the face of his farmer father. You see, no matter how far the son fled from his father, no matter how much he disregarded his father, distanced himself from his father’s place and principles, the father was never far from his son.

Now that I’ve seen that face, the face of the father peeking into the painting, I see it in the parable too. “But when he came to himself, he said, ‘How many of my father's hired servants have more than enough bread, but I perish here with hunger! I will arise and go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son. Treat me as one of your hired hands.”’ And he arose and went to his father.” The son—even at his lowest, even at his lostest—was keenly aware of the persistent presence of his father.

In the central panel, the father runs to welcome his son home. The top border depicts the various means of transportation used by the wealthy son for his flight from the father--a day and a night and another day of jet planes. The bottom border reveals his significantly slower journey home. The jet-setting has definitely come to an end--buses give way to cars to beat-up pickups to sneakers to bare feet. It is in fact on bare feet that the son walks home from the dazzling city in the desert. He trudges from yellowed grass and cactus to the green fields of a rolling farm. Still the son seems a bit hesitant, but the father runs with open arms, out onto the open road where he’s spied his son approaching. He’s already mobilized the farmhands, who follow close behind, one with a blue jacket, just like dad’s, another with a ring, a third with boots.

The father, the largest figure in the panel, dominates the center of the parable. “But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and [he] felt compassion, and [he] ran and [he] embraced him and [he] kissed him. And the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’" But the father said to his servants, ‘Bring quickly the best robe, and put it on him, and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet.And bring the fattened calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate.” It’s the father who acts—he catches sight, even though he never lost sight; he’s consumed with compassion; he runs, yes, runs; he holds him to his bosom like the baby boy he’s always been; he covers him with careless kisses; he calls, for a robe and a ring, for shoes, for celebration. The father who was persistently present even in his absence, is now fully present.

In the right panel, the disgruntled older son boycotts the banquet. The celebration is in full swing. Family and friends feast at the table on the green lawn. The band plays in the background. The older son sits on a tree stump, refusing to participate in the spirit of the occasion. He angrily, foolishly, breaks his guitar in half, refusing to share in the music, the food, the joy. A skull reminds us, it is the elder son who is now dead, dead to his father, not the younger son who was dead but is now alive. He has fled to his own far country, squandering his substance with his own brand of prodigality. He speaks to his father with the same disregard and disrespect that the younger son had acted with. “Look, these many years I have served you, and I never disobeyed your command, yet you never gave me a young goat, that I might celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, came back, you killed the fattened calf for him!’

But there looming in the upper left corner is something truly provocative--the head, the face of his farmer father. You see, no matter how hard the heart of this son has become, no matter how much he disregarded and disrespected his father, distanced himself, without moving an inch, from his father’s place and principles, the father was never far from his son.

And now that I’ve seen that face, the face of the father peeking into the painting, I see it in the parable too. The image of the farmer father looks on his older son’s anger with the same sad love and mercy as he did on the other son in the left panel. The words he spoke to the older son echo from earlier in the parable--“Son (older son, younger son, every son, every son and daughter), you are always with me (because I am always with you, far country or near), and all that is mine is yours (all you demand, all you don’t, all you spend, all you save, all you want or wish or waste). It was fitting to celebrate and be glad (for him, for me, for you, for all of us), for this your brother (yes, your brother, if my son then your brother), was dead (like you) and is alive; he was lost (like you), and is found.’” This son—even at his haughtiest, even in his holier-than-thou-est—was keenly aware of the persistent presence of his father.

Application

Reading this painting has helped me to see the parable. Now I see that what I’ve taken from God--the opportunities I’ve squandered, the relationships, self-serving, self-gratifying, just plain sinful relationships--that these things matter, but they are not the main point. Now I see that what I’ve accomplished for God--the opportunities I’ve lived up to, the service I’ve rendered, the relationships, other-oriented, sacrificial, healthy and healing relationships-- that these things matter, but they are also not the main point. The point is to focus on the father, like the painting, like the parable, the parable of the persistently present father, the father who sees us as son or daughter no matter how un-son-like we are, the father who can see us when we think we’re out of sight, the father who peeks into whatever sad situation we find ourselves, not pruriently but persistently, not condemningly but compassionately, the father who can see us when we are right under his nose, thinking we know everything, know best, about our younger siblings, our sinner siblings, about God, our too-gracious, too-merciful, too-forgiving God, about our selves, our sinful, self-righteous selves. He is the father who always welcomes us home, who always celebrates our presence, whose persistent presence we must always celebrate.

Thank you, O God, for your persistent promise to be with us always.

Thank you for your son, Jesus, who promised to be with us always.

And thank you for your spirit, and for the way you are,

through your spirit, persistently present. Amen.

What we see before us is a triptych, a three-panelled painting common in the history of Christian art. The artist of our triptych, from 2002, is James Janknegt, a contemporary American Christian painter from Austin, Texas. And the subject of the triptych is the Parable of the Prodigal Son. Just to get our bearings, let’s identify the three scenes our artist chose to illustrate Jesus’ story. On the left, from early in the parable, the younger son sits in the far country. In the center, from the middle of the parable, are the father and the servants, welcoming the younger son home from his urban exile. On the right, the older son sits in a far country of his own making, while the welcome-home cookout goes on in the background. Janknegt entitled his provocative painting, “Two Sons.” To his credit, the title recognizes that there are two sons in the story, a fact overlooked by many artists and even some preachers. Even so, I’d give it a different title. I’d call it “the Persistent Presence of the Father.”

Analysis

In the left panel we meet the younger son already in the far country. He has already demanded his inheritance, and liquidated his assets, already fled to the far country, and “squandered his substance” (a pregnant phrase if there ever was one). He has already found himself without resources and without recourse, without finances or friends or family, famished, trapped in a country not only far but beset by famine. Janknegt offers us a younger son already desperate, already despondent. The dejected son sits surrounded by the evidences and effects of his life in the far country. The far country is a far city; a red car cruises the streets amid skyscrapers that dominate the urban landscape. A billboard advertises the strip clubs around the corner, the sight of his debauchery or the object of his daydreams. He sits on the steps of the Golden Arches Cafe, his pig pen, dressed in the uniform of his below-poverty-level job. He’s been rooting, like a pig, through a tipped-over garbage can, hoping to ease his hunger on Happy Meal scraps. He ponders his condition, head cocked, chin on hand, eyeing the sign at a bus stop, a way home perhaps. All in all an interesting modern depiction of the plight of the prodigal!

But there looming in the upper right corner is something provocative--the head, the face of his farmer father. You see, no matter how far the son fled from his father, no matter how much he disregarded his father, distanced himself from his father’s place and principles, the father was never far from his son.

Now that I’ve seen that face, the face of the father peeking into the painting, I see it in the parable too. “But when he came to himself, he said, ‘How many of my father's hired servants have more than enough bread, but I perish here with hunger! I will arise and go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son. Treat me as one of your hired hands.”’ And he arose and went to his father.” The son—even at his lowest, even at his lostest—was keenly aware of the persistent presence of his father.

In the central panel, the father runs to welcome his son home. The top border depicts the various means of transportation used by the wealthy son for his flight from the father--a day and a night and another day of jet planes. The bottom border reveals his significantly slower journey home. The jet-setting has definitely come to an end--buses give way to cars to beat-up pickups to sneakers to bare feet. It is in fact on bare feet that the son walks home from the dazzling city in the desert. He trudges from yellowed grass and cactus to the green fields of a rolling farm. Still the son seems a bit hesitant, but the father runs with open arms, out onto the open road where he’s spied his son approaching. He’s already mobilized the farmhands, who follow close behind, one with a blue jacket, just like dad’s, another with a ring, a third with boots.

The father, the largest figure in the panel, dominates the center of the parable. “But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and [he] felt compassion, and [he] ran and [he] embraced him and [he] kissed him. And the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’" But the father said to his servants, ‘Bring quickly the best robe, and put it on him, and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet.And bring the fattened calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate.” It’s the father who acts—he catches sight, even though he never lost sight; he’s consumed with compassion; he runs, yes, runs; he holds him to his bosom like the baby boy he’s always been; he covers him with careless kisses; he calls, for a robe and a ring, for shoes, for celebration. The father who was persistently present even in his absence, is now fully present.

In the right panel, the disgruntled older son boycotts the banquet. The celebration is in full swing. Family and friends feast at the table on the green lawn. The band plays in the background. The older son sits on a tree stump, refusing to participate in the spirit of the occasion. He angrily, foolishly, breaks his guitar in half, refusing to share in the music, the food, the joy. A skull reminds us, it is the elder son who is now dead, dead to his father, not the younger son who was dead but is now alive. He has fled to his own far country, squandering his substance with his own brand of prodigality. He speaks to his father with the same disregard and disrespect that the younger son had acted with. “Look, these many years I have served you, and I never disobeyed your command, yet you never gave me a young goat, that I might celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, came back, you killed the fattened calf for him!’

But there looming in the upper left corner is something truly provocative--the head, the face of his farmer father. You see, no matter how hard the heart of this son has become, no matter how much he disregarded and disrespected his father, distanced himself, without moving an inch, from his father’s place and principles, the father was never far from his son.

And now that I’ve seen that face, the face of the father peeking into the painting, I see it in the parable too. The image of the farmer father looks on his older son’s anger with the same sad love and mercy as he did on the other son in the left panel. The words he spoke to the older son echo from earlier in the parable--“Son (older son, younger son, every son, every son and daughter), you are always with me (because I am always with you, far country or near), and all that is mine is yours (all you demand, all you don’t, all you spend, all you save, all you want or wish or waste). It was fitting to celebrate and be glad (for him, for me, for you, for all of us), for this your brother (yes, your brother, if my son then your brother), was dead (like you) and is alive; he was lost (like you), and is found.’” This son—even at his haughtiest, even in his holier-than-thou-est—was keenly aware of the persistent presence of his father.

Application

Reading this painting has helped me to see the parable. Now I see that what I’ve taken from God--the opportunities I’ve squandered, the relationships, self-serving, self-gratifying, just plain sinful relationships--that these things matter, but they are not the main point. Now I see that what I’ve accomplished for God--the opportunities I’ve lived up to, the service I’ve rendered, the relationships, other-oriented, sacrificial, healthy and healing relationships-- that these things matter, but they are also not the main point. The point is to focus on the father, like the painting, like the parable, the parable of the persistently present father, the father who sees us as son or daughter no matter how un-son-like we are, the father who can see us when we think we’re out of sight, the father who peeks into whatever sad situation we find ourselves, not pruriently but persistently, not condemningly but compassionately, the father who can see us when we are right under his nose, thinking we know everything, know best, about our younger siblings, our sinner siblings, about God, our too-gracious, too-merciful, too-forgiving God, about our selves, our sinful, self-righteous selves. He is the father who always welcomes us home, who always celebrates our presence, whose persistent presence we must always celebrate.

Thank you, O God, for your persistent promise to be with us always.

Thank you for your son, Jesus, who promised to be with us always.

And thank you for your spirit, and for the way you are,

through your spirit, persistently present. Amen.