Riojas' Prodigal Son, an Interpretation

by Lee Magness

PREACHING THE PRODIGAL: “While we were yet sinners, Christ died for us”

Luke 15.11-32

The Parable of the Prodigal Son is the best known of Jesus’ parables--which is just one of the reasons it may be among the most misunderstood. For all we think we know about this familiar story, there’s so much we don’t know or at least haven’t understood very clearly. For instance, why did Jesus tell this parable and to whom and for whom did he tell it? Why did the younger son want to leave home in the first place and what did he do with all that money in the far country? And what is a “prodigal” son anyway? Who does the father represent? And how did the father show his compassion—just the greeting and the gifts? And what about that older brother—what could he have done differently, what should he have done differently? Sometimes, when we have questions about familiar passages of scripture, it helps to listen to them from another perspective, to look at them through a different set of eyes.

That’s why I’d like to see what we can see in the parable of the Prodigal Son through the eyes of a wonderful contemporary artist named Edward Riojas.

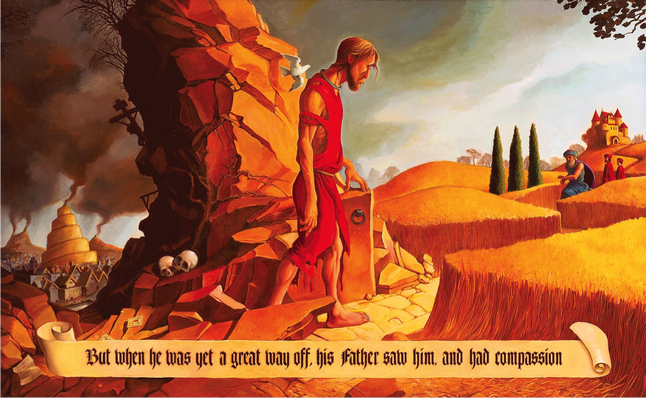

First, what do we have to learn about the far country through this artist’s eyes? Do you see the smoke curling up and clouding the sky? Do you see the dim houses, huddled in the half-light, wall to wall, no grass, no fields, no parks, no people? Do you see the skulls, grinning from the shadowed rock, bare and barren? It’s a dirty place, where humans, so eager to benefit and enrich themselves, have besmirched the sky and befouled the land. It’s a dark place, where human enterprise has blocked out the light that otherwise filled the sky and floodlit the fields and lit their lives. It’s a desolate place, isolated from the light, isolated from the life that otherwise pulsed across the planet. It’s a destructive place, destroying the earth, the sky, the human spirit itself. It’s a place of death, the death of everything given by God for the life of humankind, and the death of the humankind God gave everything to and for.

But there are still several more small but significant clues--there are the towers, and the cards, and the coins.

The towers are temples, ziggurats, Mesopotamian pyramids build by the Babylonians to worship the gods—the god of the sky humanity has polluted, the god of the water humanity has poisoned, the god of the land humanity has profaned. So life in the far country is a life of idolatry, of putting our faith in anything and everything other than God, the God of light and life and love. The cards are tarot cards, magic mirrors onto the future, meager attempts to manipulate the trajectory of human life, to forge our own paths to the divine. So life in the far country is a life of sorcery, of fixing our hope on anything and everything other than God, the God of yesterday and today and tomorrow. And the coins are, well, coins, the currency of contemporary culture, the worthless slugs we slip again and again into the slots labeled “happiness” and “fulfillment” and “meaning,” the little gods in whom we trust. So life in the far country is a life of illusion, of placing our trust in anything and everything other than God, the God who is worthy and who gives us our worth. So, now I see, see the far country a little more clearly. The prodigal life, the wasteful life, is a life in which we waste our faith and squander our hope and throw away our trust. The far country, the prodigal life, is life without God, the ground of our existence.

Second, what does this powerful painting by Riojas have to teach us about the effects of the far country on the younger son? Look at his clothes, look at his posture, look at him, just look at him! His once rich, red robe is now ragged, tattered, torn, threadbare. His body is bent, strong but bent, barely able to support his slouching shoulders, his drooping head. His once youthful face is now weathered, worse for the wear, worn, beaten, bearded beyond his years. His hair hangs, like his clothes, like his skin, like his arms, like his eyes, lowered, not just unwilling but unable to look up the lane that his feet feel as if for the first time. And look, just look at that left hand, poised on the post! The gate is gone, the way is clear, no bar, no lock, no barrier. So why do his pointed fingers pause on the post? Why does he stand flatfooted at the gate? Why does his gaunt frame freeze at the front door?

The far country could not have corrupted his image of his father. According to Jesus’ parable, he never forgot his father, even in the far country. He remembered that his father was still his father, even in the far country. He remembered his father’s kindnesses and generosity, even in the far country. So why does he hesitate now, now when he sees through his lowered lashes his father running, running to meet him, running through the waving wheat, through the bright-scented air, running from the welcoming house on the hill? He hesitates because the far country has corrupted his image of himself. He is what he owns, his worth is what he’s worth, his personhood is defined by his productivity, meaning is defined by the deities he manufactures. The far country has almost convinced him that he is either a god, creating himself in his own image, or an animal, a pig, intelligent but unclean, part of the herd but hermetically sealed off, stymied, alone, lost. So, now I see, see the prodigal son a little more clearly. The prodigal life, the wasteful life, is a life in which we squander not only our substance but our self, a self created by God, created to live in relationship with God. What the prodigal needs is to come to himself, which is to reclaim the reality of life in God, the sphere of our existence.

And finally, is there anything in this beautiful painting that can shed some light for us on the nature of the father? Some things are obvious--the father lives in the light, but it’s not unapproachable light, it’s a warm and welcoming light; and the father provides out of his abundance, from wheat fields, their full-grown grain standing ready to be reaped; and the father runs, runs, mind you, down the well-paved lane, not hunkered down in that massive mansion now a hut on the horizon; and the father has already engaged his servants in a parade of gifts, even before the prodigal has repented.

Other things are not quite so obvious--like the white dove shadowing the slumped shoulder of the son. Could it be anything other than the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of God, the persistent presence of God that has been with him every step, every wingbeat of the way, to the far country, in the far country, returning from the far country? So, now I see, see the father a little more clearly. He waits, waits patiently for the return of his recalcitrant son. And he welcomes, eagerly, prodigally, extravagantly. But he does more than wait or welcome. He also wings his way, persistently providing his spiritual presence, wherever we may wander, the destination of our existence.

But where is the elder son in this artistic depiction of the parable of the Prodigal Son? Well, the elder son of the parable is missing in action, back home in the lap of luxury or out reveling in the ripe-unto-harvest. But there is an elder son, the true elder son, in this painting. Did you spot him? He hangs on a cross, in the darkness, on a bare and barren rock, a place of the skull, hanging out over the valley of the shadow of darkness and dirtiness and desolation and destruction and death, yes, even death. For while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us, an elder brother, sent at a dear and desperate cost from the ever-present, ever-pained father of all us prodigals.So now I see, see that Jesus not only told this story, but that he insinuated himself into the silences—father, son, spirit, and savior--in a way that I had not clearly seen until now.

What do we have to learn from this fresh look at this familiar parable, from looking at the parable through this painting? First, we have learned that the far country, our sin, our life on the dark side, is characterized not only by the way we have dingied and dirtied and destroyed and defiled and put to death everything that is living and lovely around us, but even more by the way we have misplaced our faith, our hope, and our trust, misdirected our worship, by worshiping the signs of God in the world around us and in ourselves, the very signs and selves we simultaneously destroy, instead of worshiping only the loving and living God. This is, surprisingly enough, a parable about idolatry.

Second, we have learned that the younger son, both in the depths of depravity and on the very doorstep of reconciliation, is plagued not so much by a mistaken understanding of God but of himself. Even in the midst of rebellion against God, as we live out our bent lives, we remember God, we miss the benefits of a close relationship with God. It’s ourselves we forget, that we are created in God’s image and likeness, that we share God’s nature, that we were meant to live intimately with the loving and living God. This is, surprisingly enough, a parable not just about coming back to God but about coming to ourselves.

Third, we have learned that the father, God, does not dwell in unapproachable light. God is approachable and, more amazing yet, God approaches. God sprints toward the darkness, trailing the light, his love, in his wake, able to wait for and at the same time welcome our return. And we have learned that the God who waits and runs and welcomes, is in fact with us in all our wandering all along the way. This is, surprisingly enough, a parable about the God who doesn’t wait.

Finally, we have learned that, when we are the elder son, we are often shamefully absent from the celebration, but there is an elder son hanging in there with all us prodigals, insinuating himself into the silences of our dark lives. It is he, the one who bends over the whole bent world, whose pain marks the pathway from darkness to light. This parable of Jesus is, surprisingly enough, a parable about Jesus.

Luke 15.11-32

The Parable of the Prodigal Son is the best known of Jesus’ parables--which is just one of the reasons it may be among the most misunderstood. For all we think we know about this familiar story, there’s so much we don’t know or at least haven’t understood very clearly. For instance, why did Jesus tell this parable and to whom and for whom did he tell it? Why did the younger son want to leave home in the first place and what did he do with all that money in the far country? And what is a “prodigal” son anyway? Who does the father represent? And how did the father show his compassion—just the greeting and the gifts? And what about that older brother—what could he have done differently, what should he have done differently? Sometimes, when we have questions about familiar passages of scripture, it helps to listen to them from another perspective, to look at them through a different set of eyes.

That’s why I’d like to see what we can see in the parable of the Prodigal Son through the eyes of a wonderful contemporary artist named Edward Riojas.

First, what do we have to learn about the far country through this artist’s eyes? Do you see the smoke curling up and clouding the sky? Do you see the dim houses, huddled in the half-light, wall to wall, no grass, no fields, no parks, no people? Do you see the skulls, grinning from the shadowed rock, bare and barren? It’s a dirty place, where humans, so eager to benefit and enrich themselves, have besmirched the sky and befouled the land. It’s a dark place, where human enterprise has blocked out the light that otherwise filled the sky and floodlit the fields and lit their lives. It’s a desolate place, isolated from the light, isolated from the life that otherwise pulsed across the planet. It’s a destructive place, destroying the earth, the sky, the human spirit itself. It’s a place of death, the death of everything given by God for the life of humankind, and the death of the humankind God gave everything to and for.

But there are still several more small but significant clues--there are the towers, and the cards, and the coins.

The towers are temples, ziggurats, Mesopotamian pyramids build by the Babylonians to worship the gods—the god of the sky humanity has polluted, the god of the water humanity has poisoned, the god of the land humanity has profaned. So life in the far country is a life of idolatry, of putting our faith in anything and everything other than God, the God of light and life and love. The cards are tarot cards, magic mirrors onto the future, meager attempts to manipulate the trajectory of human life, to forge our own paths to the divine. So life in the far country is a life of sorcery, of fixing our hope on anything and everything other than God, the God of yesterday and today and tomorrow. And the coins are, well, coins, the currency of contemporary culture, the worthless slugs we slip again and again into the slots labeled “happiness” and “fulfillment” and “meaning,” the little gods in whom we trust. So life in the far country is a life of illusion, of placing our trust in anything and everything other than God, the God who is worthy and who gives us our worth. So, now I see, see the far country a little more clearly. The prodigal life, the wasteful life, is a life in which we waste our faith and squander our hope and throw away our trust. The far country, the prodigal life, is life without God, the ground of our existence.

Second, what does this powerful painting by Riojas have to teach us about the effects of the far country on the younger son? Look at his clothes, look at his posture, look at him, just look at him! His once rich, red robe is now ragged, tattered, torn, threadbare. His body is bent, strong but bent, barely able to support his slouching shoulders, his drooping head. His once youthful face is now weathered, worse for the wear, worn, beaten, bearded beyond his years. His hair hangs, like his clothes, like his skin, like his arms, like his eyes, lowered, not just unwilling but unable to look up the lane that his feet feel as if for the first time. And look, just look at that left hand, poised on the post! The gate is gone, the way is clear, no bar, no lock, no barrier. So why do his pointed fingers pause on the post? Why does he stand flatfooted at the gate? Why does his gaunt frame freeze at the front door?

The far country could not have corrupted his image of his father. According to Jesus’ parable, he never forgot his father, even in the far country. He remembered that his father was still his father, even in the far country. He remembered his father’s kindnesses and generosity, even in the far country. So why does he hesitate now, now when he sees through his lowered lashes his father running, running to meet him, running through the waving wheat, through the bright-scented air, running from the welcoming house on the hill? He hesitates because the far country has corrupted his image of himself. He is what he owns, his worth is what he’s worth, his personhood is defined by his productivity, meaning is defined by the deities he manufactures. The far country has almost convinced him that he is either a god, creating himself in his own image, or an animal, a pig, intelligent but unclean, part of the herd but hermetically sealed off, stymied, alone, lost. So, now I see, see the prodigal son a little more clearly. The prodigal life, the wasteful life, is a life in which we squander not only our substance but our self, a self created by God, created to live in relationship with God. What the prodigal needs is to come to himself, which is to reclaim the reality of life in God, the sphere of our existence.

And finally, is there anything in this beautiful painting that can shed some light for us on the nature of the father? Some things are obvious--the father lives in the light, but it’s not unapproachable light, it’s a warm and welcoming light; and the father provides out of his abundance, from wheat fields, their full-grown grain standing ready to be reaped; and the father runs, runs, mind you, down the well-paved lane, not hunkered down in that massive mansion now a hut on the horizon; and the father has already engaged his servants in a parade of gifts, even before the prodigal has repented.

Other things are not quite so obvious--like the white dove shadowing the slumped shoulder of the son. Could it be anything other than the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of God, the persistent presence of God that has been with him every step, every wingbeat of the way, to the far country, in the far country, returning from the far country? So, now I see, see the father a little more clearly. He waits, waits patiently for the return of his recalcitrant son. And he welcomes, eagerly, prodigally, extravagantly. But he does more than wait or welcome. He also wings his way, persistently providing his spiritual presence, wherever we may wander, the destination of our existence.

But where is the elder son in this artistic depiction of the parable of the Prodigal Son? Well, the elder son of the parable is missing in action, back home in the lap of luxury or out reveling in the ripe-unto-harvest. But there is an elder son, the true elder son, in this painting. Did you spot him? He hangs on a cross, in the darkness, on a bare and barren rock, a place of the skull, hanging out over the valley of the shadow of darkness and dirtiness and desolation and destruction and death, yes, even death. For while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us, an elder brother, sent at a dear and desperate cost from the ever-present, ever-pained father of all us prodigals.So now I see, see that Jesus not only told this story, but that he insinuated himself into the silences—father, son, spirit, and savior--in a way that I had not clearly seen until now.

What do we have to learn from this fresh look at this familiar parable, from looking at the parable through this painting? First, we have learned that the far country, our sin, our life on the dark side, is characterized not only by the way we have dingied and dirtied and destroyed and defiled and put to death everything that is living and lovely around us, but even more by the way we have misplaced our faith, our hope, and our trust, misdirected our worship, by worshiping the signs of God in the world around us and in ourselves, the very signs and selves we simultaneously destroy, instead of worshiping only the loving and living God. This is, surprisingly enough, a parable about idolatry.

Second, we have learned that the younger son, both in the depths of depravity and on the very doorstep of reconciliation, is plagued not so much by a mistaken understanding of God but of himself. Even in the midst of rebellion against God, as we live out our bent lives, we remember God, we miss the benefits of a close relationship with God. It’s ourselves we forget, that we are created in God’s image and likeness, that we share God’s nature, that we were meant to live intimately with the loving and living God. This is, surprisingly enough, a parable not just about coming back to God but about coming to ourselves.

Third, we have learned that the father, God, does not dwell in unapproachable light. God is approachable and, more amazing yet, God approaches. God sprints toward the darkness, trailing the light, his love, in his wake, able to wait for and at the same time welcome our return. And we have learned that the God who waits and runs and welcomes, is in fact with us in all our wandering all along the way. This is, surprisingly enough, a parable about the God who doesn’t wait.

Finally, we have learned that, when we are the elder son, we are often shamefully absent from the celebration, but there is an elder son hanging in there with all us prodigals, insinuating himself into the silences of our dark lives. It is he, the one who bends over the whole bent world, whose pain marks the pathway from darkness to light. This parable of Jesus is, surprisingly enough, a parable about Jesus.